By Anoma Pieris

When we set out in search of John Knox six months ago, my partner Athanasios and I were seeking information on Aboriginal service personnel who had served in World War II; several of whom were buried in war graves cemeteries in Asia.

John Knox’s was one of three known graves at Kranji Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery in Singapore, a beautifully laid out lawn of headstones overlooking the Straits of Johore with an art deco monument resembling an airplane. Athanasios had written a definite book on the Kranji architect Colin St Claire Oakes.

But at the time we were unaware that there were Aboriginal servicemen buried at that cemetery. A chance photograph and a trail of information led us to Leslie John Knox (Les) at Narrabri, a phone call and over 1000 kilometres away in rural New South Wales where the weather is decidedly warmer than winter in Victoria.

En route to Narrabri, stopping to gaze at the magnificent Warrumbungles we were made aware of the Cooee March recruitment drive from Gilgandra to Sydney during World War One that had gathered diggers from country towns along the route. Australia’s intersecting military histories are laid out across this landscape.

Les is John Knox’s grandson, a Moree-born Gamilaroi/Bigumbul man who spent his early childhood at Toomelah near Boggabilla. Both his father, artist Cyril Knox and cousin country singer Roger Knox, represent the creative side of the family and are well known.

Les, who recently retired as a shire councillor is better known for his many sporting feats, which have earned him a spot in the Narrabri Wall of Fame and more famously took him on the commemorative 1988 all-Indigenous cricket tour to England where the squad had an audience with Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth inside Buckingham Palace.

Interspersed among cricketing and other sporting stories and personalities covering his involvement in practically all known major sports in Australia, Les told us a deeper more personal story of family sacrifice.

Anyone familiar with Dawn Magazine, may recollect the cheeky boy seated on a tree stump on the front cover of the April 1956 issue. Behind him stretches the road to Toomelah a small Aboriginal community in the Moree Plains Shire, somewhere between Boggabilla and Goondiwindi. Established as an Aboriginal reserve in 1937 it has since the 1970s been under self-management by the local Aboriginal Land Council.

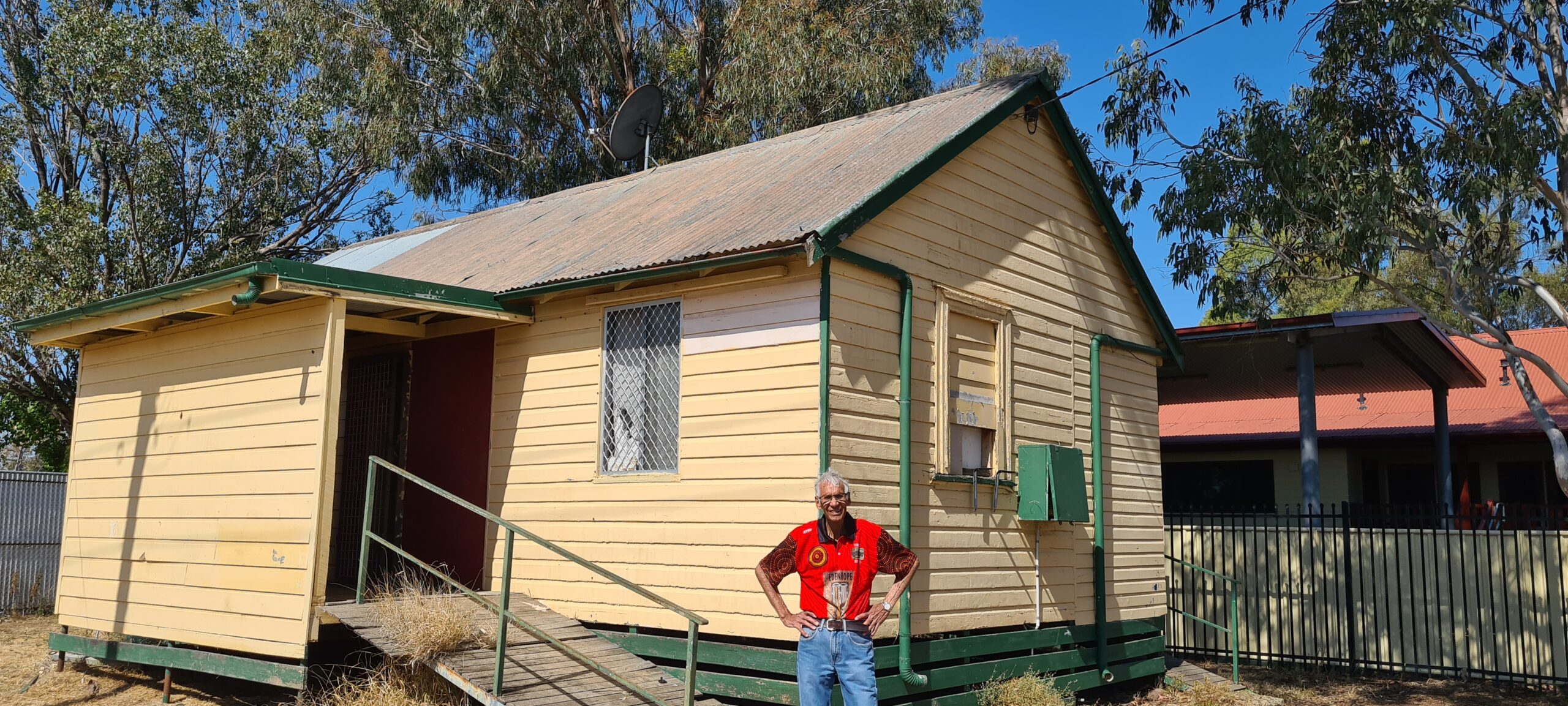

Les took us there to show us the house in which he lived until age seven, and described the large square in which they played broom-handle cricket in a happy childhood. It is remarkable that so many men from this small community went away on overseas military expeditions to fight for Australia.

Les learned of his grandfather, John’s service quite accidentally, having stumbled on some papers and medals in an old trunk at the back of his father’s house in Narrabri in 2003. He took these to the Regimental Tailor at Tamworth where they identified his grandfather’s service record.

John Knox was identified as a labourer but was also a minister and 39 years old at the time.

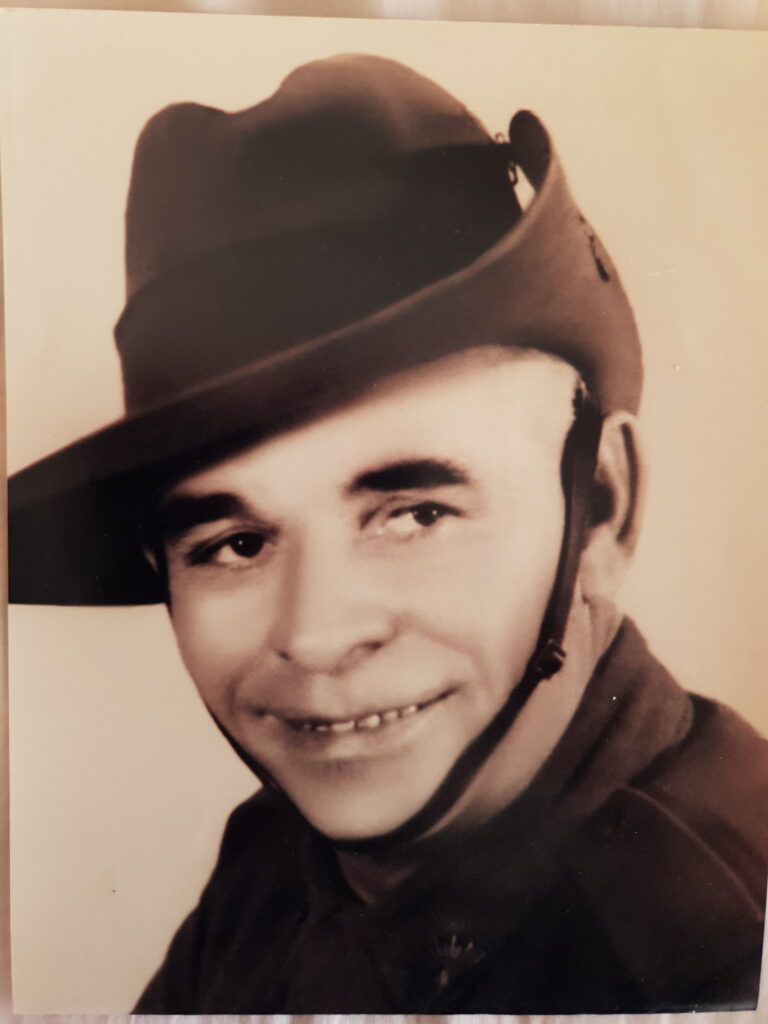

The late John Knox.

“His last letter to my grandmother named seven people from Toomelah, and states ‘I have not seen them for a number of days and I don’t know where they are’’,” he tells us.

When they refused to enlist him in New South Wales because he was Aboriginal, he walked all the way to Warwick over one-hundred and eighty kilometres across the border and enlisted as an ‘Australian’. John Knox enlisted as a private in the 2/26th Australian infantry battalion on July 11, 1940 which trained at the Grovely and Redbank camps before moving on to join the 2/29th and 2/30th at Bathurst – part of the 8th Division sent to Malaya.

Private John Knox, QX11089 died on August 31, 1942 in Changi Prison seven months after the Fall of Singapore when he was taken prisoner along with 52,000 others. He is commemorated in four different memorials in addition to Kranji War Cemetery: on the roll of honour in Canberra’s Australian War Memorial commemoration courtyard, at the Ballarat Prisoner of War Memorial in Victoria, and most significantly at Toomelah in a war memorial dedicated in 2009 to 24 persons who have served from there, the first such memorial in an Aboriginal community.

Among them is Flight Sergeant Leonard Waters, the only Aboriginal pilot to fly in World War II, and George E Cubby also from the 2/26th battalion who died at Kanburi in Thailand. On our visit to Toomelah on October 20, Maxine McGrady told us of the annual Anzac Day ceremonies which brings visitors and family back to the community.

At Boggabilla, Les introduced us to Terrence Stacey, a Vietnam veteran who was one of three people, Les (Bluey) Lang and David Williams in opening the memorial there. Terence served overseas for 11 months fighting in the tropical jungle, much like John Knox did in Malaya. “They told me Aboriginal people couldn’t enlist,” says Les, “otherwise I would have joined up and at that stage I didn’t know about my grandfather or that Terry had signed up.”

What compelled individuals like John Knox to enlist? Was it adventure? Opportunity? Poverty? Courage? Patriotism? A series of recent exhibitions, since 2018, with titles like “For Country for Nation” (Australian War Memorial, Canberra) and “For Kin and Country” (Shrine of Remembrance, Melbourne) ponder these questions seeking to rectify a grave misconception that Aboriginal people did not participate in these formative overseas expeditions that overdetermined Australian national character and marked the landscape of every country town.

The exhibitions display personal memorabilia of the few thousand individuals who fought on behalf of Australia in different theatres of conflict – in Europe, the Pacific, Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan. But there are so many gaps in our knowledge of their service because few were identified by race, and many had Anglicised names, or concealed their identities.

In the army they were all equal, comrades in arms, their units remembered like the 2/26th at the Bathurst camp memorial, but those who returned were often

neglected, denied soldier settlement land grants, and left to fend for themselves and families who had struggled in their absence. These stories need telling.

We teach at the University of Melbourne’s school of architecture where students are introduced to Indigenous content through design problems, for example, a memorial to Indigenous service personnel like the one created in Canberra. Or an RSL club welcoming to and adapting to Indigenous cultural practices and needs.

We seek advice from Indigenous cultural advisors in framing our assignments and involve them in teaching. Understanding the experience of Indigenous service people who left Australia to fight in Asia, in countries that many of our international students come from is important for exploring the contradictions that underly ideas of loyalty, patriotism, social responsibility and equality. We try to convey to them a fuller understanding of Australia through these many insights.

The stories of the ancient landscape of Gamilaroi country in northeastern New South Wales with its volcanic crags, glaciers, and sawn rocks are too deep for us outsiders to decipher, nor do we have the right to tell them. Touring with Les they come to life.

We are acutely aware that the path that we take intersects with Charlie Perkins 1965 Freedom Ride the famous protest against segregation at the Dubbo Hotel, The Moree Pool, the Walgett RSL, and so on. Much has changed since that earlier confronting bus ride, just two years before a successful referendum for constitutional change.

We follow this path sobered by recent events. Visiting the local RSLs for dinner, Les shows us a different more welcoming, and family-friendly setting. The RSL, the pub, and the sports club anchor the rural townscape. Les, who grew up in Narrabri town, and played in all three of its sporting ovals is a comfortable and familiar, part of the community.

Acceptance is hard-won and not always forthcoming. A disturbing storyline weaves through Gamilaroi Country – of an earlier history of frontier wars. Les takes us to the Myall Creek Massacre and Memorial Site and we walk along the pathway mirroring the rainbow serpent’s form. With each step, we learn of a different piece of the story, of the 28 Wirrayaraay elderly men, women and children who were murdered by 10 convict stockmen led by a squatter on June 10, 1838 while their men folk were away on another station.

In this instance, an exception in Australia’s history, 12 men who committed this heinous act were taken to trial, found not guilty, re-arrested, tried again and seven of them eventually hanged. “This is the first place of reconciliation”, says Les. In 2000, 162 years after the event, the memorial was opened as an acknowledgment of the truth of this shared history, between descendants of those murdered as well as of perpetrators, in an important act of truth-telling.

The Myall Creek story is integral to our understanding of the military histories of Australia on which this nation has been built. With the Australian War Memorial taking on the challenge of representing the frontier wars it is, perhaps, the most significant such site in the region. But to fully understand how these stories are nested one within the other and in turn, in the physical landscape, they need to be interpreted by someone from Country. Without Les, we would have gained only a partial history gleaned from books and websites with no means for interpreting this many-layered landscape.

To order photos from this page click here