By Richard Barry OAM

Not all of our Anzacs carried a weapon.

Today I speak of those folk – mainly girls many of whom volunteered to go to South Vietnam during the longest war involving Australians in the 20th century – a war that divided the nation like no other.

I speak of the nurses who saw terrible things and keep seeing those things today.

We are constantly bombarded by vivid pictures from the Middle East and Ukraine of what wars can do to people.

If we look hard enough, you’ll see what the nurses and doctors are confronted with almost every day.

What about these nurses?

This is my personal reflection. Nurses have dealt with the face-to-face realities of war – the sick, the wounded, the dead and dying.

They worked behind the lines in field hospitals, on hospital ships and transports during two great world wars.

In many cases they had the same lack of necessities as their patients, and gave their all in the line of duty.

In my experience – in Vietnam, more than 200 civilian nurses, 100 Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) nurses and 43 young girls from the Royal Australian Army Nursing Corps (RAANC) served their country as part of the Australian Army’s involvement in that war from 1966 to 1972.

Service nurses were also involved in the evacuation of casualties back to Australia.

A huge proportion of those still alive today have in recent years been diagnosed with psychological disorders. The nurses tour of duty ranged from a few months up to 13 months, but most stayed a year.

Many veterans did two tours and a few completed three tours – 36 months! Just incredible!

Advances in medical technology and methods of patient care saved many lives.

‘Dust-off’ helicopters lifted the wounded from the battlefield, and often within one hour the men were in a hospital. I vividly recall one chopper nicknamed the ‘Band-Aid Special.’

This radically slashed battle-casualty mortality rates, but meant the nurses had to deal with more and more patients.

Many of the injuries were “traumatic amputations “caused by anti-personnel mine explosions and booby traps, but gunshot and shrapnel wounds remained a common form of battle casualty.

The work was very demanding, and the hours long.

Intensive care nurses undertook at least 12-hour shifts each week.

During the 1968 Tet Offensive some toiled for 14 hours straight.

Most had been given little preparation for what they would encounter when they arrived, and some initially got a hostile reception from male medical staff.

When they returned to Australia, they had to contend with public anti-war sentiment and a hostile media – the same as we did when we came home from combat operations.

The overriding concern for most of the army nurses was the condition of us troops – ‘our boys’ they often called us.

They were just like our sisters.

The injuries from shellfire, explosions, gunfire, and anti-personnel mines were horrific – so bad, in fact, that in any other circumstance many would never be treated and they would have died before reaching hospital.

That was the benefit of having helicopters. When someone was either killed or wounded, we sent a radio message and the chopper would locate our grid reference (and agreed smoke colour) within minutes.

One Vietnam Army Nurse I spoke to on October 3, 1992, at the Dedication of the Australian Forces Vietnam National Memorial Anzac Parade Canberra recalled, “… as soon as there was a contact, a siren would go all over the hospital as far down as the beach at Vung Tau, and anyone who was off-duty would either turn up or ‘phone in to see how many wounded were involved and if they were needed.

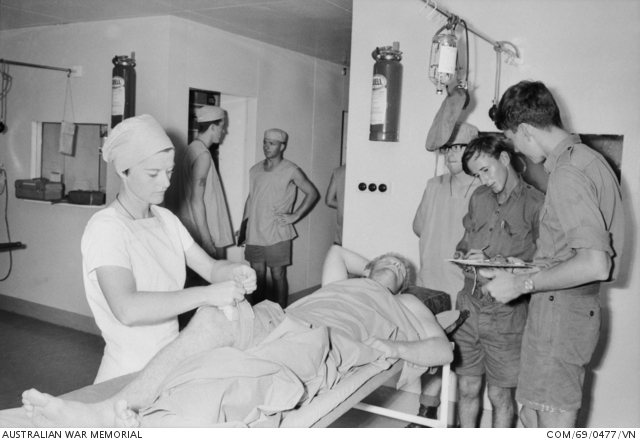

When the wounded boys came in on a stretcher, there’d be someone standing by with a pair of scissors and they would cut straight through their shoelaces right up their clothes so you could lift them to examine their back (for shrapnel wounds) before they were put to bed.

The back was examined and then the front and the anaesthetist would be there to put the drip in and straight away the pathologist would take blood for cross-match and everyone else had their own jobs to do, and the wards men would be inside scrubbing the theatre, and they would take the patient through to the theatre sometimes within twenty minutes of them being wounded.”

You can only imagine why my blood boiled when certain people thought it was okay to spray graffiti over our Vietnam and other most scared memorials in Canberra.

A terrible disgraceful act to the memory of those young men who died fighting against oppression in a foreign country in the defence of freedom and democracy.

A sacrilege.

Once, while routinely cutting through an injured digger’s shoelaces in triage, nurse Trish Ferguson was appalled when his foot came away in her hand – only the boot had held it in place.

Sometimes the injuries were less obvious – shell fragments had to be meticulously removed, along with bits of mud and scrub, before minuscule perforations of the abdomen could be detected.

There was always a lighter side. Many blokes who stepped on a mine which shredded their legs and severely damaged the lower part of their body often wanted assurance from the nurses that their manhood was intact.

Few of the nurses had ever seen anything like this before.

Despite the seriousness of their injuries, the soldiers’ survival rate was very high in South Vietnam – 2.6 per cent of those admitted to hospital died, about half the mortality rate in the Second World War.

I had firsthand experience with these nurses on two occasions.

The first was when aviation fuel blew up in my face in Nui Dat and my head and arms were covered in bandages for a few weeks.

The nurse at the Regimental Aid Post was brilliant and very caring saying that my girlfriend will still love my pretty face when I get home (I’ve been with this same girl for 58 years).

The second time was when my very good mate from Inverell received a bullet wound to his chest.

I visited him in the Field Hospital at Vung Tau. He was well looked after and survived to come home. The nurses were so caring and in reality, they took the place of our mothers who were back home sick with worry.

The Australian girls earned only two-thirds of what a male Officer of similar rank earned.

The American nurses were aghast at the discrepancy, but the Aussie girls made no protest – after all, it was the same situation back home in civilian hospitals.

Programmed to put others first, the nurses soldiered on, shouldering the enormous burden of their sick and dying ‘boys’ – for the girls who had the harrowing intimacy of sharing someone’s last moments, there could be no forgetting.

As one nurse tried to explain: “That act of helping someone is more intimate than anything and once you have done that, you can never be ordinary again.”

I recall disembarking from a C130 Hercules at Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) Tan Son Nhat Airport from Nui Dat in Phuoc Tuy Province mid-September 1969.

We walked over to the United Services Organisations (USO) Canteen to wait for our connecting flight back to Australia when we bumped into a big group of US army nurses dressed in immaculate uniforms. They were great girls and laughed and giggled at our Aussie accents.

They told us they were waiting to be sent to the front line up north.

Later I found out that some of these vibrant young American girls never made it home.

We eventually embarked on a Qantas 707 to be back in Australia within hours, a far cry from the 11 days it took to sail from Townsville on the aircraft carrier HMAS Sydney months previously.

Later I learnt that the immediate past president of the Narrabri RSL sub-Branch Gary Mason OAM was on the same voyage in May 1969 – he was a young sailor working feverishly in the bowels of the aircraft carrier. What a coincidence.

We had no idea we were to face a hostile media and members of the public spitting and calling us “baby killers.”

What a terrible welcome home! Luckily, they were in the minority but it was still disgraceful – that had never ever occurred with returning troops from both World Wars.

I took one last look before take-off and will never forget the scene that appeared before my eyes as we taxied out to the runway.

There was a long line of rolling luggage trailers being pulled by a small tractor across the tarmac except it wasn’t carrying suitcases – it was carrying many metal coffins to be loaded onto a Continental jet bound for the United States.

What a waste of young lives and what for?

I ended up back in Narrabri unexpectantly and shocked my dear Dad. We had no warning of our departure date and there were no telephones. He hugged me tightly and I spent the next few weeks lying low and keeping quiet about where I had been. I have a niece working as a nurse locally and I am quite sure she would rise to the occasion in 2024 if confronted with similar situations. The tradition continues.

And in the years since the Vietnam War, men and women across all branches of the Australian Defence Force continue to treat, heal and support civilians and military personnel alike both in conflict and in peace.

We thank them for their service and sacrifice. I shall never forget the Vietnam nurses.

It is most appropriate today that we pay homage to these brave nurses who still suffer badly from PTSD – Lest We Forget.

To order photos from this page click here